A REFLECTION IN HONOR OF INDONESIAN PRIMATE DAY: EXPLORING THE ORIGINS OF CRISIS

-

Date:

30 Jan 2023 -

Author:

WIT Indonesia

Opinion

Ahmad A Jabbar, Primate Conservation Activist

30 Jan 2023

It wouldn’t be overstating things to say that the commemoration of Indonesian Primate Day (HPI) in 2023 will have the subject “Every Primate Counts,” which is a simple but meaningful phrase. This is likely intended to remind us once more that, up until this point, we may have forgotten that humans belong to the primate order in terms of biological taxonomy.

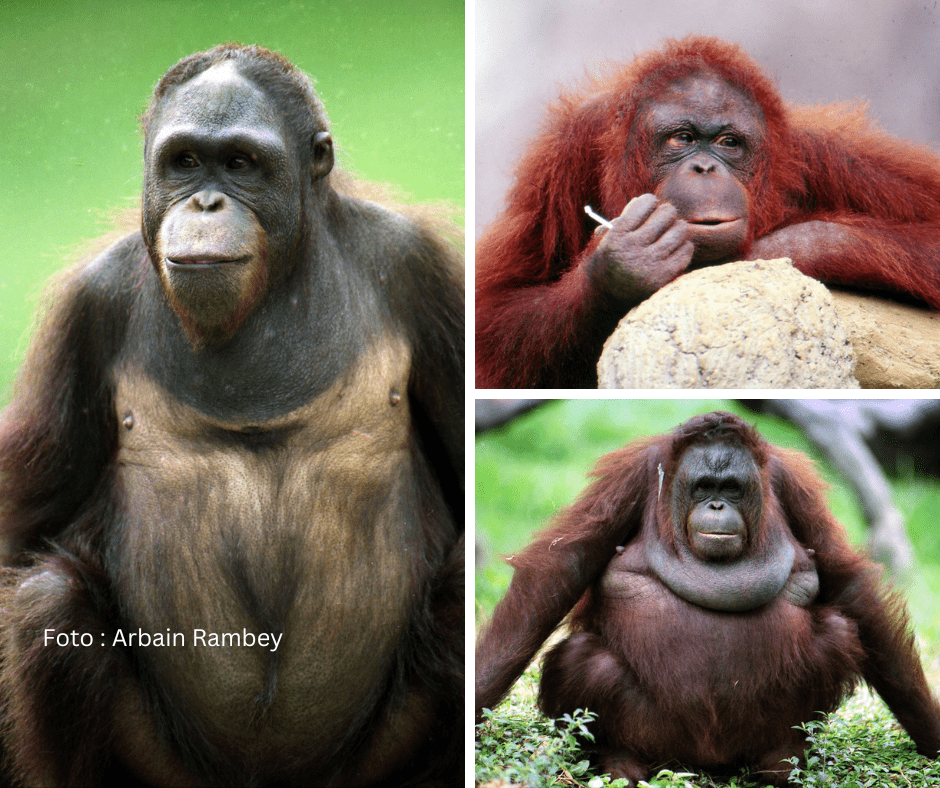

In essence, we share a tight taxonomic relationship with other primates. Consider the four great ape species that we are aware of: chimpanzees, bonobos, gorillas, and orangutans. What does each primate therefore mean? With all the existing restrictions, this work attempts to interpret it.

Anthropocene

The most recent time in Earth’s history when human actions started to have a noticeable impact on the planet’s climate and ecosystems is referred to as the anthropocene. The earth on which we dwell has undergone significant alteration during the past few millennia (Sanderson et al 2002).

Massive agricultural practices are developed in response to the rising human population in order to supply food necessities. The rate of population expansion also affects how much space and land are used for habitation, which leads to urbanization and raises the demand for energy and other natural resources.

The changes brought on by rising anthropogenic pressure gradually push us toward a crisis where the ecosystem, which includes us humans and other primates, has been harmed. This occurs as a result of anthropogenic pressure drastically diminishing the structural and functional complexity of ecosystems (Smart et al. 2006; Steffen et al. 2015; Barnosky & Hadly 2016).

There hasn’t been a consensus on the start date of the anthropocene epoch up to now. According to some experts, this era started during the time of Europe’s industrial revolution at the end of the 18th century (Zalasiewicz et al. 2008).

The argument made by Zalasiewicz and his coworkers is pretty logical given that the industrial revolution significantly altered the way people manufacture commodities. We have entered an era of industrialization characterised by the enormous use and exploitation of resources thanks to scientific and technological advancements.

Regrettably, the exploitation of non-human primates to satisfy their needs and interests results in their marginalization and, occasionally, their extinction. In the end, this one-sided preoccupation and dominance have a negative effect on mankind as a whole, which frequently manifests as crises and calamities.

We’ve recently been forced to reevaluate what is really at the heart of all these crises and how we can deal with them as a result of a number of crises that have happened and are still happening in the last decade, including the global food crisis, energy crisis, ecological crisis, and global climate crisis.

Back to Basic

Humans are frequently viewed as beings that are separate from non-human apes in a general perspective that tends to be dichotomous. This point of view is predicated on the idea that humans are the culmination or end of evolution (primates), making them unique from other living creatures.

In his famous statement, cogito ergo sum, René Descartes, for instance, underlined the difference between humans and other living creatures in their reasoning tendencies. This precept in turn gave rise to a mechanical viewpoint that sees nature as an object and sets people as its subject. According to this viewpoint, humans control nature and see themselves as the center of the universe (anthropocentric). It is believed that nature is a vast, motionless machine.

One of the greatest thinkers, Jean-Paul Sartre, represented the existentialists, who focused on the element of human consciousness. According to existentialists, the only thing that distinguishes humans from other animals and plants is their knowledge of their own existence. Moreover, the humanistic psychology point of view contends that people are moral beings. This point of view contends that it is our capacity for accountability that sets us apart from other animals.

A Muslim scholar from the 20th century named Murtadha Mutahhari presents an alternative perspective on all the ideas advanced by earlier western philosophers. He provided a multi-dimensional definition of the human, which basically said that, in addition to sharing physiological and instinctual similarities with animals, the main distinction between humans and animals, in his opinion, is found in the levels and dimensions of knowledge and awareness.

Animals and humans both possess knowledge and consciousness; the difference is that animal knowledge and awareness are transient and constrained, but human knowledge and awareness are able to transcend these limitations. According to Muthahari, this is what places humans at the top of the food chain for primates and other animals.

On a practical level, this potentiality can be demonstrated by the fact that people have a natural tendency to be good and have an understanding of concepts like values, ethics, and morality that are immaterial or abstract. Muthahari believes that since non-human apes and other animals do not possess knowledge, awareness, or spiritual qualities, humans are distinct from them.

What therefore is the connection between the topic of where the differences between humans, primates, and other animals are located and the theme of addressing the causes of many current crises? Here, we seek to identify and locate the crises’ internal source. The fact that we humans have a propensity to detach ourselves from other primates and isolate ourselves from them may be the cause of periodic crises.

We might no longer share the same conscious bonds with other monkey groups because of this distance and separation. So much so that we no longer consider other facets of consciousness that exist in primates other than humans when making decisions about attitudes and behaviors. Most of our actions and behavior as humans today may rely on anthropocentric calculations, if not entirely.

As was already mentioned, anthropocentrism holds that anything that benefits people only has worth if it also benefits other living things. It is worthless by itself. Hence, nature is ultimately seen as a thing that must satisfy the wants and purposes of human primates.

We humans believe we have overcome all natural obstacles and even conquered them for our own interests once we reach the summit of knowledge acquisition. It is believed that all of our knowledge can address every issue that exists outside of us.

It is the time to reevaluate the idea that transcendent spirituality, which inspires people to do good things, must be balanced with human understanding. Humans will be led to morally admirable deeds like treating themselves, nature, and everything else outside of themselves by this propensity for abstract and spiritual goodness. Returning to transcendent spirituality (faith) can preserve humanity from catastrophes brought on by egoism, selfishness, domination, boundless exploitation, indifference, and separation from existence outside of himself.

In fact, both humans and non-human primates share the same level of consciousness at their respective levels and have a similar commitment to nature. The degree of our humanity is greatly influenced by our knowledge, consciousness, and free choice, all of which are present in humans to some extent. How we approach nature, as well as the acts and behaviors we choose to engage in toward it, will mainly define where we fall in the evolutionary and existential hierarchy.

Bibliography

Barnosky AD, Hadly EA. 2016. Tipping point for planet earth: how close are we to the edge? Thomas Dunne Books, New York

Muthahhari, 1993. Manusia Sempurna. terj. M. Hashem, Jakarta: Lentera

Muthahhari, 1992. Perspektif Al-Qur’an Tentang Manusia dan Agama, terj. Bandung: Mizan

Muthahhari, 1992. Kritik Islam terhadap Faham Materialisme. terj. Achsin M. Muzdakir. Jakarta: Risalah Masa

Muthahhari, 1981. The Human Being in the Qoran. Teheran: Minitry of Islamic Guidance.

Sanderson EW, Jaiteh M, Levy MA, Redford KH, Wannebo AV, Woolmer G. 2002. The human footprint and the last of the wild. Bioscience 52:891–904

Smart SM, Thompson K, Marrs RH, Le Duc MG, Maskell LC, Firbank LG. 2006. Biotic homogenization and changes in species diversity across humanmodified ecosystems. Proc R Soc Lond 273:2659–2665

Steffen W, Broadgate W, Deutsch L, Gaffney O, Ludwig C. 2015. The trajectory of the Anthropocene: the great acceleration. Anthr Rev 2(1):81–98