Indonesia: The World’s Laboratory for Orangutan Research

-

Date:

19 Aug 2021 -

Author:

KEHATI

Written by:

Didik Prasetyo, Ph.D

Professor at the Faculty of Biology and Biology Masters Program, National University of Jakarta (Universitas Nasional Jakarta)

Chairperson for Indonesian Primate Experts and Activists Association (PERHAPPI)

Happy Orangutan Day! For primate researchers or those working on anthro-biology, researches on Great Apes have become a general discussion, both in classes and in discussions related to the theory of evolution. Primates/Great Apes have also generally been introduced in elementary school lessons. But do we know when did Great Ape researches began to be conducted more seriously? Louis Seymour Bazett Leakey, a Kenyan-British paleoanthropologist and archeologist, was very interested in the human evolution theory, and sent his students to countries that are home to great apes. Leakey’s Angels or The Trimates was the name given to female researchers sent by Leakey to answer his hypotheses. These Angels were Jane Goodall, assigned to research chimpanzees in Gombe on 1960; Dian Fossey was the female researcher who researched gorillas in Rwanda on 1966; and the last one was Birutė Galdikas, assigned to research Orangutans in Indonesia on 1971. Since then, researches on great apes (Chimpanzees, Gorillas, and Orangutans) have become a widely discussed topic until today.

Since orangutan research started in Indonesia on 1971, Indonesia has owned two of the oldest orangutan research stations, namely the “Camp Leakey” Orangutan Research Station in Tanjung Putting National Park, Central Kalimantan, and the “Ketambe” Orangutan Research Station in Mount Leuser National Park. Both of these research stations are still active and have produced a plethora of international scale scientific findings. Since that time, Indonesia has developed a number of other orangutan research stations, namely: Mentoko and Prevab (Kutai National Park (NP), East Kalimantan), Cabang Panti (Mount Palung NP, West Kalimantan), Bukit Peninjau (Lake Sentarum NP, West Kalimantan), Setia Alam (Sebangau NP, Central Kalimantan), Punggualas (Sebangau NP, Central Kalimantan), Tuanan (Mawas area-Ex. PLG, HL Kapuas, Central Kalimantan), Mangku (Rungan-Kahayan, Central Kalimantan), Suaq Balimbing (Mount Leuser National Park, South Aceh), Bukit Lawang and Sikundur (Mount Leuser National Park, North Sumatra ) and Mayang (Batang Toru, North Sumatra), and these will continue to develop as science grows more advanced.

For 50 years, Indonesia has become the natural laboratory for orangutan researchers, both international researchers and globally renowned Indonesian researchers. However, long term research outcomes are assets that have yet to be optimized to support the conservation implementation of orangutans and other species in Indonesia. Latest documentations and publications from various aspects on nutrition, health, genetics, and landscape studies have given a lot of new discourses to support orangutan conservation. The current challenge is how to integrate science discourses in the implementation of orangutan conservation, and how to continually update science to address future challenges, such as climate change crisis, zoonosis potential, and finding the opportunity scheme to utilize biodiversity for the advancement of science.

Photo Didik Prasetyo

A Startling Finding

New Orangutan Type and Spread1. History records that orangutans are spread from South China to the end of Sunda Lands. The most recent spread of wild orangutans is only found in Sumatra and Kalimantan Island, including Sabah and Sarawak in Malaysia. In 2017, a new type of orangutan was found, based on the different morphology and genetics, namely Tapanuli Orangutan (Pongo tapanuliensis). With this finding, Indonesia has three types of orangutans, namely Bornean Orangutan (Pongo pygmaeus), Sumatran Orangutan (Pongo abelii) and Tapanuli Orangutan (Pongo tapanuliensis). In addition, an orangutan spread has been found in South Kalimantan, an area never reported before. Globally, the current population of wild population is 71,820 individuals, on a 17.5 million hectare habitat. There are 57,350 estimated Bornean Orangutans on a 16 million hectare habitat. Some of them share population and habitat with Bornean Orangutans in Serawak. Meanwhile, there are 13,710 Sumatran Orangutans living on a 2 million hectare habitat, and Tapanuli Orangutans are estimated to be only 577-760 individuals on a 105 thousand hectare habitat. The difference of the number of population of each orangutan type raises a new challenge in the protection of these endemic apes.

The challenge for orangutan conservation becomes quite difficult, because at least 78% of Bornean Orangutan habitat is spread outside of conservation areas (natural reserves/natural preservation areas and hunting parks), namely areas managed by forestry concessions, monocultural plantations, mining, community management areas, and Forest Management Unit (KPH) management areas. The impact of development and environmental dynamics causes their primary habitat on lowland forests to decrease. Meanwhile, orangutans prefer dry lowland tropical rainforest and swamp habitats to highland forests. The recent situation shows that the orangutan population is spread across many habitat pockets. Strong collaborative actions at the site level and policy support from the regional to national level are required to protect the orangutan population from extinction.

Orangutan Life and Reproductive Cycle2. Orangutans’ lifecycle in the wild can reach more than 50 years, and the average female orangutan is ready to give birth at the age of 14.8 years, with a fertile period of up to 45-50 years of age. Orangutans have a gestation of around 245 days. An orangutan mother raises her offspring alone. During the first year of its life, an orangutan baby is continuously carried by its mother. Even after the first year, it continues to be breastfed and carried on far trips, as it is learning to eat solid foods. The juvenile phase of an orangutan starts approximately at the age of three. An orangutan’s Inter Birth Interval (IBI) is around 7.6 years (5.5-9.3 years), but a juvenile orangutan is not fully independent yet until it reaches the age of around 7.8 years (weaning). Unlike their wild counterparts, orangutans living in rehabilitation centers and zoos have faster life and reproductive cycle. For example, a female orangutan can achieve sexual maturity in less than 12 years and has a shorter inter birth interval, which is 5-6 years. Orangutans’ slow reproductive cycle makes these apes highly at risk from habitat change and poaching.

Orangutan Energy Status3,4. As fruit-eating apes, the availability of fruits in the forest is very important for orangutans. Almost 60% of their diet are fruits from around 1,500 types of plants. However, fruit availability is not always stable in certain areas, thus orangutans need strategy in fulfilling their nutrition. From long term research on the nutritional needs of wild orangutans, it is found that during the abundant fruit season, a male orangutan needs 8,422 kcal/day and a female one needs 7,404 kcal/day. This condition differs greatly during the fruit shortage season, where a male orangutan only requires 3,824 kcal/day, while a female one needs 1,793 kcal/day. The change in daily nutritional needs in orangutans is a form of survival strategy that is adjusted to available food sources in the wild. It is also found that orangutans are not always fixed on the availability of fruits as their food source, but it can also come from leaves and plant skins.

The daily nutrition fulfillment strategy in a certain condition concludes that there is a difference in orangutans’ body mass, and it is found that the complete daily calorie needs of orangutans is as follows: flanged male orangutan (108.18 kcal/kg MBM), unflanged male (204.14 kcal/kg MBM), adult female (209.11 kcal/kg MBM), teenage male (264.95 kcal/kg MBM), and teenage female (299.03 kcal/kg MBM). This finding is also found in orangutans living in rehabilitation centers, in which nutritional availability still depends on human assistance. In conclusion, a flanged male orangutan needs daily energy intake of 83.06 kcal/kg MBM, while an unflanged male orangutan needs 121.88 kcal/kg MBM. Based on findings in the long term research on nutritional needs status and strategy of orangutans, it is concluded that flanged male orangutans require the last amount of daily energy intake compared to other age groups. This finding can change the paradigm of orangutan conservation in the wild and rehabilitation. This information on nutritional needs can directly serve as the basis to assess habitat carrying capacity in a more detailed manner.

Challenges to the Future of Orangutan Research

As technology develops and changes to orangutans’ habitat occur, the challenge of orangutan eco-biology research theme needs to be developed in a direction that can provide benefits to the human life. Researches that put basic theories forward, specifically primatology, should no longer be done in solitary, instead must be linked to various disciplines, such as remote sensing, genetics, nutrition, health, economy, even social media. Orangutan research strategy must be useful and can contribute innovations to the sustainable use of natural resources. This way, findings and/or long term orangutan research plan can be aligned with the needs of human life. By Including scientific evidence resulting from research in every decision for biodiversity conservation policy, species protection can continue to be maintained.

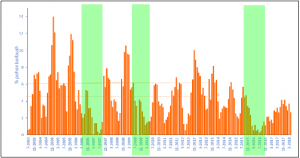

Some orangutan research themes that can be added from several long term research programs include: Climate change impact. Climate change is a result of industrial, mining, and livestock activities, as well as the loss of forest covering, and the development of modes of transportation causes rising earth surface temperature and forest fires. In 2015 and 2019, forest draught and increasing human activities had caused large forest fires in Indonesia. These forest fires affected the productivity of forest trees as the primary food source for orangutans. Based on the long term research of forest phenology in Tuanan, Central Kalimantan; the production of fruit trees had drastically decreased after the occurrence of these forest fires (Figure 1).

The behavior change dynamics and survival strategy of animals, especially orangutans, have changed the direction of orangutan research, particularly to disturbed habitats. For example changes in food type, exploring distance, and movement of Bornean Orangutan have changed significantly after the forest fires. In addition, plants’ physiology adaptation to climate change becomes a critical information in the general ecological research in Indonesia, including the role of pollinating insects (generally bees), which have been indicated to suffer from local extinction.

Zoonosis. Orangutans are biologically and physiologically similar to humans, with a similarity of DNA reaching 97%. This becomes an important issue, encouraging that orangutan researches should not only focus on their behavior, but also their relationship with human physiological health. The advancement in research technology makes it easier for researchers to study the biological cell characteristics of orangutans deeper. For instance, the current genetic analysis advancement is able to map orangutan’s genetic sub-population, which is crucial in determining conservation policy. The protein and genetic structure information can also predict the spread of viruses, such as SARS-Cov-2 in great apes, and so on. Indonesia now has at least 37 laboratories with the facility of identifying protein base pairs used in addressing the Covid-19 pandemic. In the future, using this facility in research activities on orangutan’s protein and genetic modelling serves as both an opportunity and a challenge.

Nutrition. Researches on the nutrition of orangutans and other primates to understand their adaptation pattern and health, both wild and rehabilitated orangutans, have been done within the last five years. This knowledge is essential and can serve as a reference in discussions on the health theory development in humans, for example in the research of normal intestines of plant microorganisms, related to orangutans’ reproductive and survival strategy. Modelling the use of orangutan habitats through landscape is the current research challenge in the sustainable development era. The orangutan habitat suitability analysis is very useful in mapping the appropriate habitat areas for orangutans, which can then be used in species conservation policymaking at the landscape scale. Researches of orangutans outside of conservation areas, as with those inside concession areas, also need to be done comprehensively.

Improving the Quality of Researchers. Indonesia currently has many primate researchers, particularly orangutans, with very good scientific reputation. The Indonesian Primate Congress held in 2019 has proven that Indonesia has more than 200 primate researchers. The quality and distribution of this quality of Indonesia’s primate researchers need to be improved, especially in young generation, and more specifically those within the proximity of orangutan habitats. The human resource development for orangutan researchers cannot be separated from the cooperation between various domestic and international research organizations, facilitated by the Ministry of Research and Technology/National Research and Innovation Agency (Kemenristek/BRIN), such as Utrecht University, Netherlands; University of Zurich, Switzerland; Rutgers University, USA; Boston University, USA; Exeter University, UK; York University, Canada; and others. Developing research collaboration with international parties must be based on the mutual equity and utility principle. Infrastructures for orangutan field research in Indonesia have been developed since the 1970s, and until today, there are at least 14 active orangutan research stations. The existence of field research stations must also be supported by laboratories and technological and equipment to make it easier for researchers to study deeper on Indonesia’s orangutan molecular biology. In addition, the support to build institutional capacity for local universities and research organizations through training, funding, and partnership opportunities is crucial to consider.

Multiparty Research Collaboration. The policy of conducting research in orangutan conservation is a necessity to obtain a science-based decision. The orangutan research information and data center serves as the basis to integrate accountable scientific conclusions. Collaboration between orangutan scientists/researchers and policymakers is a critical element in carrying out strategy recommendations and implementation for orangutan conservation in Indonesia, including the ones linked to multi-sectoral collaboration, evaluation of orangutan rehabilitation policy, management of orangutan population outside of conservation areas, technical aspects on animal crime law enforcement, and evaluation of human-animal conflict mitigation policy.

Strategy Recommendations for Indonesia’s Orangutan Research Policy

Based on the latest findings in orangutan research, and the growing interest from researchers to better understand Indonesian endemic apes’ survival, the following are several strategies for orangutan research policy:

- Giving priority for scientific data and results of orangutan researches carried out by Indonesian researchers as the basis to make policies regarding the protection of orangutans and their habitats, both inside and outside of conservation areas.

- Promoting government policy support in strategic science collaborations to increase intellectual property productivity, specifically scientific publications and patents, and to achieve equal partnership in international research based on mutual respect and fair and equitable mutual benefits sharing

- Providing technological upgrades in primate researches, particularly orangutan, and improving the quality of Indonesia’s orangutan researchers through multi-sectoral cooperation to attain advanced and excellent human resources.

- Establishing The Center of Excellence on orangutan research to accommodate the development of orangutan research. Ideally, an orangutan research requires long term research planning and implementation. This institution is needed to bridge past research achievements, conduct research and promote results to be developed for the advancement of science, technology, and policy reference.

Reading materials:

- Nater, A., Mattle-Greminger, M. P., Nurcahyo, A., Nowak, M. G., de Manuel, M., Desai, T., . . . Krutzen, M. (2017). Morphometric, Behavioral, and Genomic Evidence for a New Orangutan Species. Curr Biol, 27(22).

- van Noordwijk, M.A., Utami Atmoko, S.S., Knott, C.D., Kuze, N., Morrogh-Bernard, H.C., Felicity,, Caroline,S., van Schaik, C. P., and Willems E. P. (2018). The slow ape: High infant survival and long interbirth intervals in wild orangutans. Journal of Human Evolution 125: 38-49.

- Prasetyo D. (2019). Understanding Bimaturism: The Influence Of Social Conditions, Energy Intake, And Endocrinological Status On Flange Development In Bornean Orangutans (Pongo Pygmaeus Wurmbii). Dissertation. Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey. New Jersey.

- Vogel, E. R., Alavi, S. E., Utami-Atmoko, S. S., van Noordwijk, M. A., Bransford, T. D., Erb, W. M., . . . Rothman, J. M. (2017). Nutritional ecology of wild Bornean orangutans (Pongo pygmaeus wurmbii) in a peat swamp habitat: Effects of age, sex, and season. Am J Primatol, 79(4), 1-20. doi:10.1002/ajp.22618